パーム砂漠

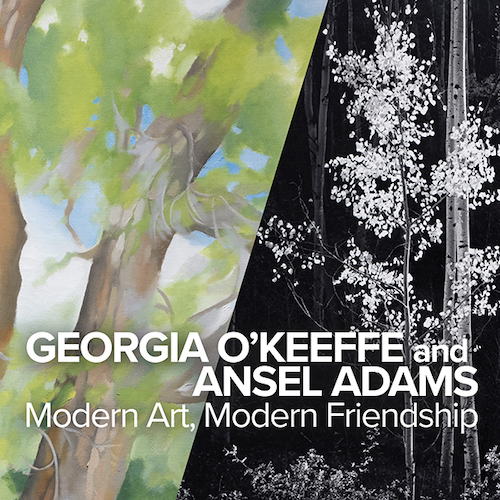

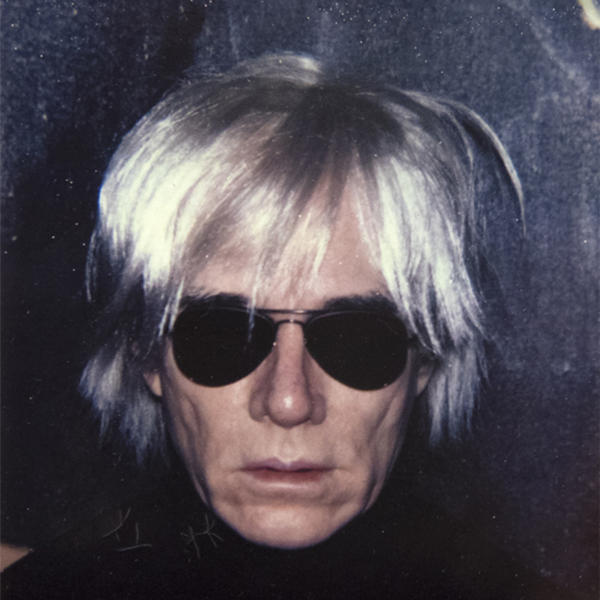

パーム砂漠のギャラリーは、エルパセオの人気のショッピング&ダイニングエリアに隣接し、カリフォルニア州のパームスプリングスエリアに位置しています。私たちの顧客は、戦後、現代美術、現代美術の私たちの選択に感謝しています。冬の間の豪華な天候は、私たちの美しい砂漠を見て、私たちのギャラリーに立ち寄るために、世界中からの訪問者を引き付けます。外の山岳砂漠の風景は、内部で待っている視覚的なごちそうに完璧な風光明媚な背景を提供します。

45188 ポルトラ・アベニュー

パーム砂漠, CA 92260

(760) 346-8926

営業時間:

月曜日から土曜日まで:午前9時~午後5時

_tn43950.jpg )

_tn27843.jpg )

_tn46214.jpg )

_tn39239.jpg )

_tn46616.jpg )

_tn28596.jpg )

_tn47464.jpg )

_tn46213.jpg )

_tn47033.jpg )

_tn40803.jpg )

_tn16764.b.jpg )

_tn47012.jpg )